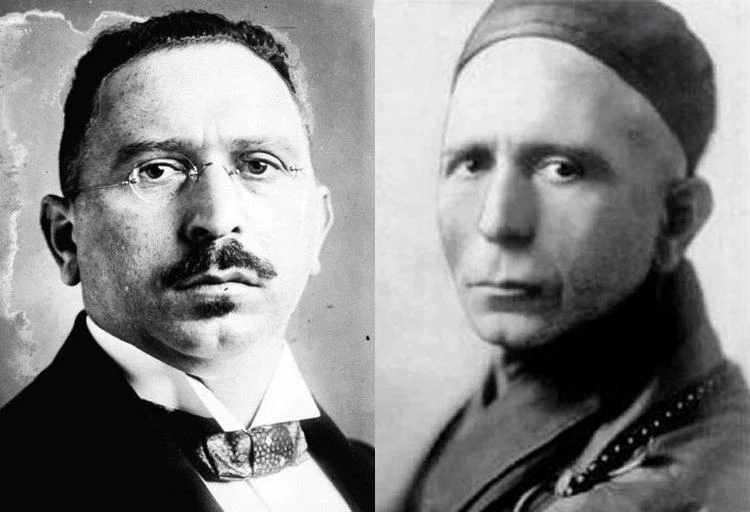

Trebitsch Lincoln – Conman Curate of Appledore

Who was this man?

He was Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln (1879–1943), one of the most colourful con-men or ‘adventurers’ of the twentieth century. And yes, for a while he was a curate at St Peter & St Paul’s church in Appledore.

Amongst other things, he was also a missionary in Canada, a Member of Parliament for Darlington, a Romanian oil magnate, a German spy, a Japanese spy, a Nazi collaborator, an adviser to Chinese warlords – and eventually, the Abbot of a Chinese monastery, proclaiming himself the new Dalai Lama. Appledore is incidental to the story, but it’s a story worth telling.

Ignácz Trebitsch (later changed to Trebitsch-Lincoln) was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Hungary. After leaving school he enrolled in the Royal Hungarian Academy of Dramatic Art, but didn’t attend classes. Instead, he sat in cafés, writing fictitious accounts of adventures in South American jungles, selling them to newspapers as genuine travel stories. He wasn’t above a bit of petty theft. In 1897, learning that the Budapest police wanted to talk to him about the theft of a gold watch, he fled abroad, ending up in London.

Finding himself short of money in the East End of London, Trebitsch was taken in by a Mission to the Jews – or maybe the Mission was taken in by him. Operating on behalf of the Church of England, the Mission was involved in promoting Christianity to poor Jewish immigrants from eastern and central Europe. Trebitsch made a favourable impression on the Reverend Lypshytz, who ran the Mission, but was soon back in Hungary – with a gold watch and chain belonging to Mrs Lypshytz.

Ecclesiastical career

Settling upon the ministry as a career option, Trebitsch converted to Christianity. He so impressed his religious instructor that he was entered into a seminary in Germany. He also found time to steal another gold watch. The devotional life proved too tough, involving physical labour and a timetable that barely left time for sleep. Looking for easier options, and ever eager to travel, Trebitsch set sail for Canada, arriving in 1900.

Having learnt of their existence in London, Trebitsch made his way to the Mission to the Jews in Montreal. This time, however, he suggested that he should be taken on as an employee. Somewhat massaging his CV, the charismatic Trebitsch got the job. Two years later, he was Superintendent of the Mission and an ordained Minister of the Anglican Church. The Archbishop of Montreal was sufficiently impressed that he thought Trebitsch might one day succeed him as Archbishop.

Trebitsch wasn’t content with the financial rewards of his work. His oratory was flamboyant and persuasive, but he hadn’t attracted wealthy patrons to the Mission. On a personal level, he had married a woman he had met in Germany, expecting a substantial dowry that was not forthcoming. Complaining bitterly about the size of his stipend, Trebitsch returned to England. He hadn’t converted any Jews to Christianity and the Mission was in financial disarray.

Back in England, Trebitsch somehow contrived a meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury. As ever, he made a favourable impression and in 1903 the Archbishop appointed him curate in the parish of Appledore-with-Ebony. If all went well, he would be examined and ordained a priest.

Trebitsch was in Appledore for about a year, under the supervision of the Reverend Hall. He arrived without his wife, lodging at Gusbourne Farm. His wife and new son joined him, but it is not clear where the family then lived. The curate’s wife found Appledore pleasant but damp. The villagers, she said, were “very nice, though inquisitive” – as they might well have been, given the unlikely nature of their new curate.

His sermons, delivered with a pronounced Hungarian accent, were eloquent and dramatic. They were largely improvised, with preparation limited to selecting a text and giving it a few minutes thought. Generally, Trebitsch seems to have been under-stimulated by the life of a curate in Appledore. He failed his examination for the priesthood, and was soon to take a very different path.

Trebitsch and the Chocolate Millionaire

Back in London, Trebitsch changed his name by deed poll to Ignatius Timothy Tribich Lincoln. He was unsuccessful in applying for a job with a temperance society, but in the process had the great good fortune to encounter one of the most notable men in Britain – and one of the wealthiest.

Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree was an industrialist, philanthropist and social reformer, strongly influenced by his Quaker religion. Rowntree’s surveys had revealed the depth of poverty in Britain and he was keen to investigate conditions in mainland Europe. Having overstated his gift for languages, Trebitsch secured the post of private secretary to Rowntree and became a social analyst. Even better, he was introduced to the Foreign Office with the request that they assist his enquiries. With letters of introduction to British Ambassadors, Trebitsch set off for Europe.

With few limits on his expenses, Trebitsch spent the next three years travelling in fine style, whilst acting in an imperious manner and infuriating every British official he met. Back in London, the Foreign office had a thickening file of complaints from British Ambassadors. In fairness to Trebitsch, he did complete his survey and he did produce the report requested by Rowntree. The accuracy of the report had to be taken largely on trust but Rowntree was happy with his work.

So happy, in fact, that he lent Trebitsch in excess of £10,000 (£1.2 million in 2019) so that he could set himself up in business. There was no security for the loan, and quite possibly no repayment schedule.

Trebitsch Lincoln, Member of Parliament

With Rowntree’s support, Trebitsch was adopted as Liberal candidate for Darlington in 1909, even though he was still a Hungarian citizen at the time. He was further supported by a local newspaper owned by Rowntree. Remarkably, he won the seat, having persuaded a sufficient number of the electorate that the policies of his opponent could reduce them to eating horse meat. A speech in the House of Commons later so enraged the Austrian government that it leaked details of his past as a watch thief. Trebitsch left the political arena and Rowntree realised that his million pound loan was unlikely to be repaid.

International Entrepreneur

With petty theft, religion and politics behind him, Trebitsch went into the oil business. Making the most of his brief political career, and of his Rowntree connection, Trebitsch found institutional and private backers for a company that would exploit the Romanian oil fields. Naturally, he lived well while accruing investors’ funds, particularly so in a mansion next to the royal palace in Bucharest. With smart offices in London and Bucharest, and with a royal seal of approval from the King of Romania, all looked bright – but none of the oil wells produced a drop of oil. With the business failing, Trebitsch took out a loan guaranteed by Seebohm Rowntree – except that Trebitsch had forged the letter of guarantee on National Liberal Club stationery. Investors lost everything. Guilty of fraud, Trebitsch spent some time in a Romanian prison.

Double Agent

With World War 1 approaching, and reduced to living in a boarding-house, Trebitsch thought he might make a living as a spy. He offered his services to British intelligence, and on being turned down made a similar offer to German intelligence. The German services didn’t take him too seriously but gave him some harmless information he could pass to the British as a trial run. Trebitsch went back to the British with the suggestion that he could be a double agent. He was turned down again, and also learnt that he was being investigated for fraud. Before he could be arrested, and leaving his wife and family behind, he sailed to America.

Disappointed in his hope that the German Embassy in New York would provide him with a salary, Trebitsch turned to writing articles for newspapers, as he had done in Hungary. The articles, sensational in nature, detailed his career as one of the world’s greatest master-spies. Embarrassed by the revelation that a former British MP was supposedly a German spy, the British government sought his extradition to answer charges of fraud.

Held in custody, Trebitsch immediately offered to work for American intelligence, exposing the German spy network in the USA. He said he could also decode encrypted German communications to Berlin. Incredibly, the Americans seemed to believe him. He was set up in a government office, to which he travelled with a guard, and was given two assistants. He lived well, hosted dinner parties in restaurants – and was forever just on the brink of cracking the German codes. Trebitsch also found time to write a book, entitled ‘Revelations of an International Spy’, in which he recast his adventures going back to his time as a researcher for Seebohm Rowntree. The book’s first edition sold out in three months. And then, whilst at a restaurant with his guard, Trebitsch went to the lavatory and vanished. Back in England, the Kent Messenger ran a report headlined: ‘Escape of the Appledore Curate’ and speculated that German agents may have been involved.

Trebitsch was at large for thirty-five days, during which time he gave a press conference, announcing that he would soon be continuing his personal war against the British from Asia. When apprehended, he fought extradition on the grounds that British charges of forgery were an excuse to shoot him as a spy. Somewhat embarrassed by their previous gullibility, the Americans deported him. Found guilty of fraud, Trebitsch spent the next three years in Parkhurst Prison.

With customary grandiosity, Trebitsch spent his time in prison thinking of ways in which he could bring about the downfall of the British Empire.

Trebitsch and the Proto-Nazis

Deported from England at the end of his sentence, Trebitsch went to Germany and entered the world of German right-wing politics. Despite being Jewish, and openly so, he made an impression on Colonel Max Bauer, a rabid anti-Semite who was plotting a right-wing revolution in Germany. However unlikely it might seem, Trebitsch became Bauer’s right-hand man. They were united by a love of intrigue and a hatred of Britain. Trebitsch didn’t like the fact that Britain hadn’t recognised his genius, Bauer hated any country that was party to the terms of the Versailles Treaty of 1918. For financial support, Trebitsch seduced a wealthy woman from whom he secured a large loan – which he never paid back.

In 1920, and just a few months after leaving Parkhurst prison, Trebitsch and Bauer became central figures in the Kapp Putsch, a right-wing coup that seized control of Germany. Trebitsch was appointed Director of Foreign Press Affairs which mostly amounted to censorship and propaganda. The putsch was almost comically chaotic and lasted five days. On the fifth day, two young men had flown up from Munich, keen to join in. One of them was Adolf Hitler. Trebitsch and Hitler were within yards of each other at one point, but Trebitsch seems not to have noticed – or he would have made something of it later.

The leaders of the Putsch, including Trebitsch, melted away into ‘The White International’, a confederacy of the far right operating in Bavaria, Austria and Hungary, their numbers bolstered by German ‘Freikorps’ commanders and White Russians. Bavarian officials and the Hungarian government provided safe haven, false identities and passports. The leading figures of The White International were anti-Semitic, some of them murderously so, and yet most of them came to put their trust in Trebitsch Lincoln.

Secrets for Sale

Trebitsch came to realise two things about The White International – they weren’t certain to achieve their revolutionary aims, and some of them were exceptionally dangerous men who were starting to doubt him – and some of those wanted him dead. He left, and he took with him an archive of documents detailing all of their activities and plans. Trebitsch did the rounds of consulates and embassies, and for once he had credible information for sale. The Czechoslovak government advanced him a large sum of money, sharing some of the information with other governments. The British, who knew Trebitsch for what he was, dismissed it as fantasy. The Czechs took him off the payroll but released the documents to the world’s press. The White International tried to track him down and kill him for revealing their conspiracy, the Czechs put him on trial for making it up.

Ultimately, a lack of evidence kept Trebitsch out of jail. The White International was real and their conspiracy could have led to war – but they were exposed by a known fraudster, weakening the case against them. One or two of its members, however, were still quite likely to kill Trebitsch for his treachery. Refused a visa that would have allowed escape to America, Trebitsch sailed there anyway using a false identity. Typically, while crossing the Atlantic, he befriended an American millionaire who lent him £15,000. Apprehended and deported from America, Trebitsch headed for China.

Trebitsch and the Chinese Warlords

China was then a place of competing fiefdoms under the control of what might be called ‘warlords’, some of whom had western military and commercial advisers. Within weeks of arriving, Trebitsch was adviser to Chinese general Yang Sen, and went on to be adviser and arms merchant for at least two other generals. Travelling on false papers, Trebitsch accompanied Chinese delegations to Europe where they were seeking loans and business deals. Remarkably, Trebitsch arranged meetings with Colonel Max Bauer, his former co-conspirator in The White International that he had betrayed. The deals and loans never materialised and Trebitsch somehow made his way back to America.

Trebitsch the Buddhist Monk

Trebitsch didn’t stay long in America, but long enough to write five magazine articles, one titled: ‘Lincoln, World War Spy, Plotted to Control China’. He returned to China for a few months but his next significant appearance was as Dr Leo Tandler, an Austrian Buddhist monk in Ceylon. From his cell in a small monastery, Trebitsch learnt that his eldest son had been convicted of murder and sentenced to death. Ignatius Lincoln was a soldier in the British army who had attempted to commit a robbery whilst drunk. Discovered in the act, he shot dead the occupant of the house.

Trebitsch was granted permission to return to Britain, but would only be allowed entry if he arrived before the execution. He only managed to get as far as Holland, and from there he sailed to America (on a forged passport), hoping to travel on to Tibet. With travel to Tibet virtually impossible, Trebitsch settled in China.

Trebitsch spoke of having had a mystical experience in Tientsin in 1925, and it was to Tientsin that he returned in 1927. He was ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1931. It is not clear how he was supporting himself in the intervening years, other than by giving occasional lectures. He used various aliases but was also happy to reveal his true identity. He travelled quite widely, both in China and beyond, and incredibly, on a steamer from Peking to Hong Kong, he bumped into Colonel Max Bauer… who was now a military adviser to the Chinese government.

One thing that Trebitsch did work on was his autobiography. Published in 1931, ‘The Autobiography of an Adventurer’ went on sale in Germany, England and America. There are signs of it being heavily edited by his publisher, but Trebitsch now denied that he had ever been a spy, and reversed his opinion of England, saying that it was the ‘one real bulwark of civilisation’.

In May 1931, Trebitsch was ordained a Buddhist monk, and would now be known as Chao Kung, or The Venerable Chao Kung, as Trebitsch preferred. He would, he said, no longer be interested in politics, espionage, subterfuge, or anything like that…

Trebitsch Lincoln – or Abbot Chao Kung of Shanghai

Trebitsch adopted Chinese dress, became a vegetarian and followed Buddhist practices. However, Shanghai in the 1930s was a hotbed of international conflict and Trebitsch couldn’t help but pay attention to that, especially the territorial ambitions of the Japanese. He still travelled, and in 1932 attracted thirteen European novices keen to learn from the Master. He gave himself the title of Abbot, and the novices gave their worldly goods to the Abbot. A year later, the thirteen novices had reduced to six. Some were disenchanted by his tyranny, some by his seduction of one of the nuns. Undaunted, Trebitsch attracted new supporters, including a Baroness and the widow of the richest foreigner in Shanghai.

Return of the International Spy

Trebitsch was sixty at the outbreak of World War II. Japan had occupied much of Shanghai since 1937. Intrigue, disorder and terror were all around. Trebitsch produced pro-Japanese propaganda, quite possibly on behalf of the Japanese. Both Tibetan Lamas (Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama) had died, leaving a spiritual and political vacuum. Trebitsch proposed himself as a replacement for both, because only the Abbot Chao Kung could bring peace. There were some indications that the serial plotter might be losing the plot. Meanwhile, his retinue of disciples had dwindled to two and he was living in a boarding house.

Trebitsch got in touch with the Nazis. His proposal was that he should travel to Berlin for a meeting with Hitler. He would explain how his ambition of becoming the leader of Tibetan Buddhism could be allied with Hitler’s interests in China, Tibet and India. He could broadcast from Tibet for the Nazis, turning Buddhists against British influence. The proposal reached Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop but was rejected, not least because Trebitsch was Jewish.

Curiously, despite Shanghai becoming ever more dangerous and chaotic, Trebitsch’s personal circumstances seemed to improve. Post-war investigation of another ‘adventurer’ revealed that Trebitsch ran Buddhist study sessions, to which he invited notable people from the Chinese, English and American communities. Gaining the trust of the notables, information of interest was forwarded to the Japanese. Trebitsch was also said to be involved in arms smuggling, diverting weapons intended for Chinese nationalists to the Japanese. And despite von Ribbentrop’s rejection of his grand plan for Tibet, Trebitsch was still an informant for the Gestapo in Shanghai. As one of his biographers said: “Whatever the exact details, it is plain that during the year after Pearl Harbor Trebitsch made hay while the rising sun shone.”

The End

Things changed in Shanghai. The Japanese interned foreign nationals, German intelligence services were under new management. As powerful contacts left the scene, Trebitsch was reduced to being a stateless person vulnerable to arrest. He might have managed to lay low, but laying low didn’t come naturally to Trebitsch Lincoln.

Trebitsch wrote to Hitler. He told Hitler to stop exterminating Jews, and if he didn’t, he would reveal details of Germany’s secret weapons to the British. Shortly afterwards, Trebitsch seemed to vanish, but a friend found him in hospital. He was weak, and asked for food to be brought to him, personally prepared. The friend was to bring food every day. The next day, Trebitsch had been moved to a private room and the friend was forbidden to visit. Trebitsch died a few days later on the 6th of October 1943, aged 64. Officially, he died following an operation for an intestinal complaint. Shanghai rumour said that Nazi High Command had asked that the Japanese poison him.

And so?

Conman or deluded narcissist? A biographer (see below) has speculated that Trebitsch Lincoln might have been suffering from a bi-polar disorder. Certain things do fit, but it is maybe too tempting to superimpose a diagnostic pattern on his behaviour. There may have been times when he deceived himself before deceiving others, but that’s not quite the same thing as mental disorder. Maybe he was just Trebitsch Lincoln – a man sufficiently grandiose that the only thing that mattered was Trebitsch Lincoln.

There may have been one constant thread in his life – some kind of call to religion, whether it was as a Curate in Appledore or as a Buddhist Abbot in China. Maybe religion was a suitable vehicle for his grandiosity (and fertile ground for deception), but maybe there was something genuine too. The jury will always be out on Trebitsch Lincoln.

This article draws on several sources, but chiefly:

‘The Secret Lives of Trebitsch Lincoln’ by Bernard Wasserstein (Penguin Books, 1989)

The book is out of print but used copies are easy to find.

Download the booklet here